His kingdom for a mouse: PBS' revelatory Walt Disney doc

09/14/15 01:14 PM

By ED BARK

@unclebarkycom on Twitter

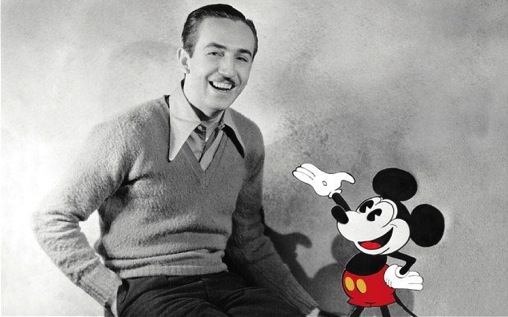

Mickey Mouse. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Disneyland. They’re just three of the many voyages and visions of the enterprising Walt Disney. And had he done absolutely nothing else, that’s far more than a full life’s work.

PBS tries and in very large part succeeds in encapsulating this extraordinary pathfinder in Walt Disney, an ambitious two-part, four-hour documentary airing under the prestigious American Experience banner. It premieres Monday, Sept. 14th and continues the following night (at 8 p.m. central in D-FW on KERA13).

“He’s either the man who ruined American culture and brought all of this fake-ness into our lives or he’s the man who inspired us and gave us hours and hours of entertainment,” Disney biographer Neal Gabler says at the close of Hour 4.

Well, there are a few in-betweens. But whatever one thinks of the Disney Company’s white bread corn, sprawling commercialism and vigilant protection of its product, the ingenious guy who started it all was anything but a hack or copycat. He aspired to artistry and created new forms of filmmaking that dazzled at the time and still pretty much do.

Monday’s Part 1, the more wondrous of the two, is captivating in its depictions of the rise of Mickey Mouse (star of the first animated talkie) and the slow flowering of Snow White into a previously unfathomable “cartoon” combination of laughter and pathos at feature film length.

Gabler, the production’s featured talking head, can be faulted at times for a full-of-himself certitude and a play actor’s delivery. But he also seems to hit much the head. And on the subject of Snow White, Gabler crisply notes that the young Disney had a central question in mind: “Can you make people cry over a drawing?” Yes, he could.

Produced/directed by Sarah Colt and narrated by actor Oliver Platt, Walt Disney has the full cooperation of the Disney estate, which made a treasure trove of vintage footage available. Still, it’s not entirely a glowing tribute, with ample time spent on his dictatorial bent, company hierarchies, “Commie” hunts, fractious relationship with his parents, battles with older brother Roy and even an emotional meltdown brought on in 1931 by over-work and insecurities.

In the latter instance, it’s quite something to hear Disney say in his own words, “I had a helluva breakdown. I went all to pieces.” It prompted him to at last take an extended vacation with his wife, Lillian, the one who came up with the name Mickey after her husband initially intended to affix the world’s most famous mouse with the considerably less than magical name of Mortimer.

As a kid in the 1950s -- and as a TV critic in training who didn’t know it at the time -- my two big Disney obsessions were his series of small-screen Davy Crockett adventures and the “Spin and Marty” after-school serials popularized on The Mickey Mouse Club. Both came after his acknowledged early “Big Five” -- Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Bambi and Dumbo -- had long since hit movie theaters.

Only Snow White became a smash hit in its initial release. The other films, products of Disney’s meticulous ways and budget run-overs, served to put his studio on the brink of bankruptcy while Snow White, despite its universal acclaim, failed to make the list of Oscar’s 1938 Best Picture nominees. He instead received an honorary statue that year from child star Shirley Temple. “Which is crap,” says art historian Carmenita Higginbotham, paraphrasing a very dismayed Disney while also clearly speaking for herself.

Walt, the dreamer and innovator, had an able partner in Roy, the pragmatic fundraiser, bookkeeper and “all-around utility man” who remained a sucker for his kid brother’s enthusiasm if not his business acumen. Roy was the first Disney in Los Angeles, relocating from the Midwest for health reasons and becoming a door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman. The older brother obviously is not a focal point of a documentary titled Walt Disney. But he certainly could be the subject someday of Roy: The Forgotten Disney. He outlived Walt by five years and postponed his retirement to preside over the completion of Orlando’s Walt Disney World and its then futuristic Epcot Center.

One of the early joys of the documentary is seeing a beaming Walt and future wife Lillian at Roy’s wedding. Walt of course mugs for the camera, but in a way that’s embraceable during a time when he saw his possibilities as endless.

Part 1 ends on a notably more somber note, the May 1941 strike by Disney studio workers after the boss had further alienated them at a mass meeting in which he demanded that “the lot of you” stop complaining and work harder for advancement and higher wages. A picket sign from those times shows an angry-looking Mickey Mouse with the caption, “Daddy Disney Unfair To His Artists.”

Roy ended up settling the strike while Walt took an extended trip abroad to remedy his “case of the DDs. Disillusionment and discouragement.” He found the admiration he craved in South America.

Walt returned to oversee another pet project, Song of the South, a post-Civil War blend of animation and live action that became best known for actor James Baskett’s performance of “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” as the benevolent Uncle Remus. Disney consulted an array of black activists on how the sensitive material should be handled, but “took the notes and then trusted his own instincts,” narrator Platt says.

The upshot: Baskett, who received an honorary Oscar in 1948, wasn’t invited to the film’s 1946 premiere in Atlanta because the theater didn’t allow blacks inside. Disney simply went along with this and later was rebuked by both the NAACP (one protester carried a “Heil Disney” sign) and the film critic for The New York Tiimes, which generally had been impressed with his work. Not this time. “The master and slave relation is so lovingly regarded in your yarn,” the critic wrote, “that one might almost imagine that you figure Abe Lincoln made a mistake.”

But Disney rebounded, as he always did. The box office hit Cinderella returned the studio to animated glory during the time that Walt was in the firmer grips of his most audacious undertaking -- the “Magical Kingdom” of Disneyland. Seeking to raise the initial $5 million budget for the theme park, Disney offered to host a weekly prime-time TV series in return for his seed money. CBS and NBC balked, but ABC (then a distant No. 3 in the ratings) decided to bite. The film’s detailed look at how Disneyland came to be is the high point of Part 2. It opened in July of 1955 on a sweltering hot day. But the lines and crowds, as stunning overhead film shows, were beyond enormous.

Walter Elias Disney died on Dec. 15, 1966 of lung cancer at the age of 65. As he once noted, the avuncular Walt Disney seen on TV didn’t have the vices of the real one: “Walt Disney doesn’t smoke. I smoke. Walt Disney doesn’t drink. I drink.”

In the end, Walt Disney succeeds as a bracingly retold fairy tale come true for a man of initial little means who felt deprived of a happy childhood and then very much doted on his own two daughters. He aimed to please -- mainly himself. But the common touch seldom eluded his grasp.

For better or worse, says Gabler, “he understood a whole lot about us.”

GRADE: A-minus

Email comments or questions to: unclebarky@verizon.net